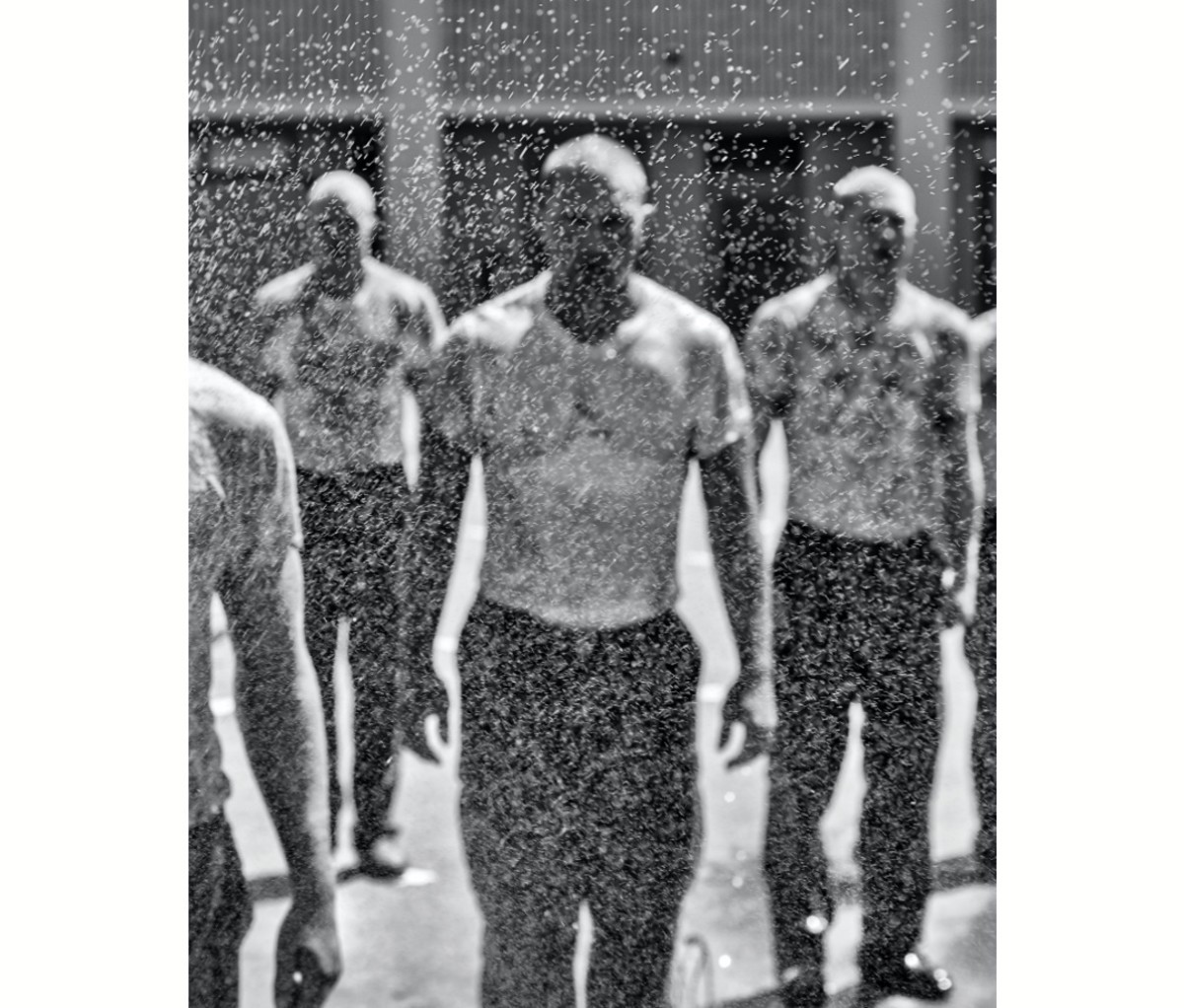

For generations, the U.S. Navy SEALS (Sea, Air, and Land) have set the standard for military special operations. Relied on for the toughest missions, these men are as notorious as their training, which begins at Naval Amphibious Base Coronado off the coast of California. Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training, or BUD/S for short, is the crucible in which SEALs are made, but the 24-week course, the first that SEAL candidates must endure, is actually only a fifth of the nearly two and a half years it takes before a man goes on his first mission.

The first phase, BUD/S, assesses candidates’ endurance and conditioning, water competency, camaraderie, and grit, culminating in “Hell Week.” The challenge has captivated men for years, and for good reason: Of an average 170-person class, around 30 make it to Week Five. Such severe attrition of some of the fittest men in the world is notable in its own right, but their day-to-day ordeals are something that has to be seen to be believed.

Darren McBurnett, age 50, a 24-year SEAL veteran, knows it better than almost anyone, having survived his own BUD/S, then returning to document the experience as a photographer and instructor prior to his retirement in 2017. He witnessed firsthand what it takes to survive arguably the most extreme military service in the world. “Everyone wants to be a Navy SEAL at the bars on Friday,” McBurnett says. “Once you get in there and realize how hard it is, all that goes away.”

McBurnett’s first book, Uncommon Grit, follows the first four weeks of Navy SEAL BUD/S training. Captured over 12 months and comprising more than 22,000 images, he was a man possessed—a camera in each hand, running behind, alongside, and in front of the most ambitious men in the military. Knocks came; he remembers being run over by boats, and at one point an expensive camera rig got swept from his hands and fell to the bottom of the sea. But he’s used to dealing with adversity, a story which he tells through images in Grit. He spoke with Men’s Journal to discuss what he learned along the way—and what you should know—about responding the the obstacles you’ll encounter in life.

1. Cut the Excuses

McBurnett saw a pattern while training and again while documenting candidates: “A lot made excuses,” he says. To leave the program, all candidates need to ring the bell and provide their reason for departure on their exit paperwork. “The biggest one, the most common is, ‘This job isn’t for me.’ ”

“Yes, this job is for you,” McBurnett says, “but you never got far enough in to see if you liked it or not.” What they were saying no to was the physical discomfort it takes to become a SEAL—the early-morning training, the cold water, the blisters so severe “chunks of skin are falling off.” In order to do all the “cool” stuff, like firing advanced weaponry and jumping out of airplanes, you had to deal with the short-term discomfort—and most can’t. “Most quit immediately when things get hard. That’s the kind of people we don’t want.” Lean into the discomfort. That persistence will always lead to greater things.

2. Shatter Your Ceiling

When other candidates see men quit, there’s an inward-looking, self-pitying look that spreads like poison. Once that seed is planted, it’s easy to go down the same route. McBurnett and other instructors’ jobs were to motivate by adding further suffering. It may seem counterintuitive, but by instigating a downward spiral, it can shock someone back to the team mentality. Remedial training, like doing thousands of pushups is not punishment per se. “It’s to let them know, ‘You still had the energy to keep going.” Ideally, it’s to demonstrate firsthand there’s always more left in the tank—an additional few reps, a faster lap. That fires them up, to see how much they can take. It’s what separates the men who are having a bad day—and everyone has a bad day, which is not a fatal condition—from those who don’t have the mental fortitude required to be a SEAL.

3. Believe in Your Inner Grit

“Every once in a while, you’ll have one of those unicorns show up,” McBurnett says. They’re the men who seem to get illogically stronger as they go through BUD/S. But they’re rare. It’s the guys who look like extras in 300—the ones who clock the fastest obstacle course laps, lead the runs, and swim laps around their peers—who drop out almost immediately upon reaching Hell Week. Take away warmth, sleep, cleanliness, and even air, and, to paraphrase a Johnny Cash song: ‘What’s all them muscles gonna do?’ The reality is, when the going gets tough, the true measure—the uncommon grit—of a man comes out. “It’s the mental war between the ears,” he says, that’s the most important characteristic of any SEAL candidate.

4. Utilize Your Team

Just making it to Hell Week, a misnomer for the five and a half days in the fourth week of BUD/S training, is an accomplishment. But to make it to its peak takes more than just being a pullup stud or part fish. “You need that sense of teamwork,” McBurnett says, which motivates you to push through your own pain and sleep-deprived haze to care about the men to your left and right. “That’s when you start to develop,” he adds. “You succeed as a team and you fail as a team.” More than conditioning, more than the possession of some of the most cutting-edge gear, it’s this characteristic that has both defined SEALs for generations and continues to fuel their successes. True, he says, there’s a long road of training ahead after Hell Week, but if you can make it past, you’ve demonstrated that you possess this critical tool in your toolset—and that’s a start.